05/06/2025

Circular Economy and planetary boundaries

*Prof. Dr. Edson Grandisoli, from the Circular Movement

The book Silent Spring (1962), written by American biologist Rachel Carson, marks the beginning of global environmentalism, even though concern for environmental issues existed before her time. Since then—63 years ago—the environmental agenda has gained ground, leadership, and countless initiatives in all countries, seeking pathways and alternatives toward a fair and inclusive socioeconomic development that considers the boundaries of a unique, fragile, and finite planet.

From being an externality, the environment has taken center stage, making it clear that there is no economy without people, and no people without the environment. Despite this relationship seeming obvious, what we witness is quite the opposite, as there is not a single indicator that demonstrates a truly positive human impact at scale. In other words, despite advances in environmental policies and practices, they still fall far short of what is needed to conserve what remains and regenerate what has already been lost.

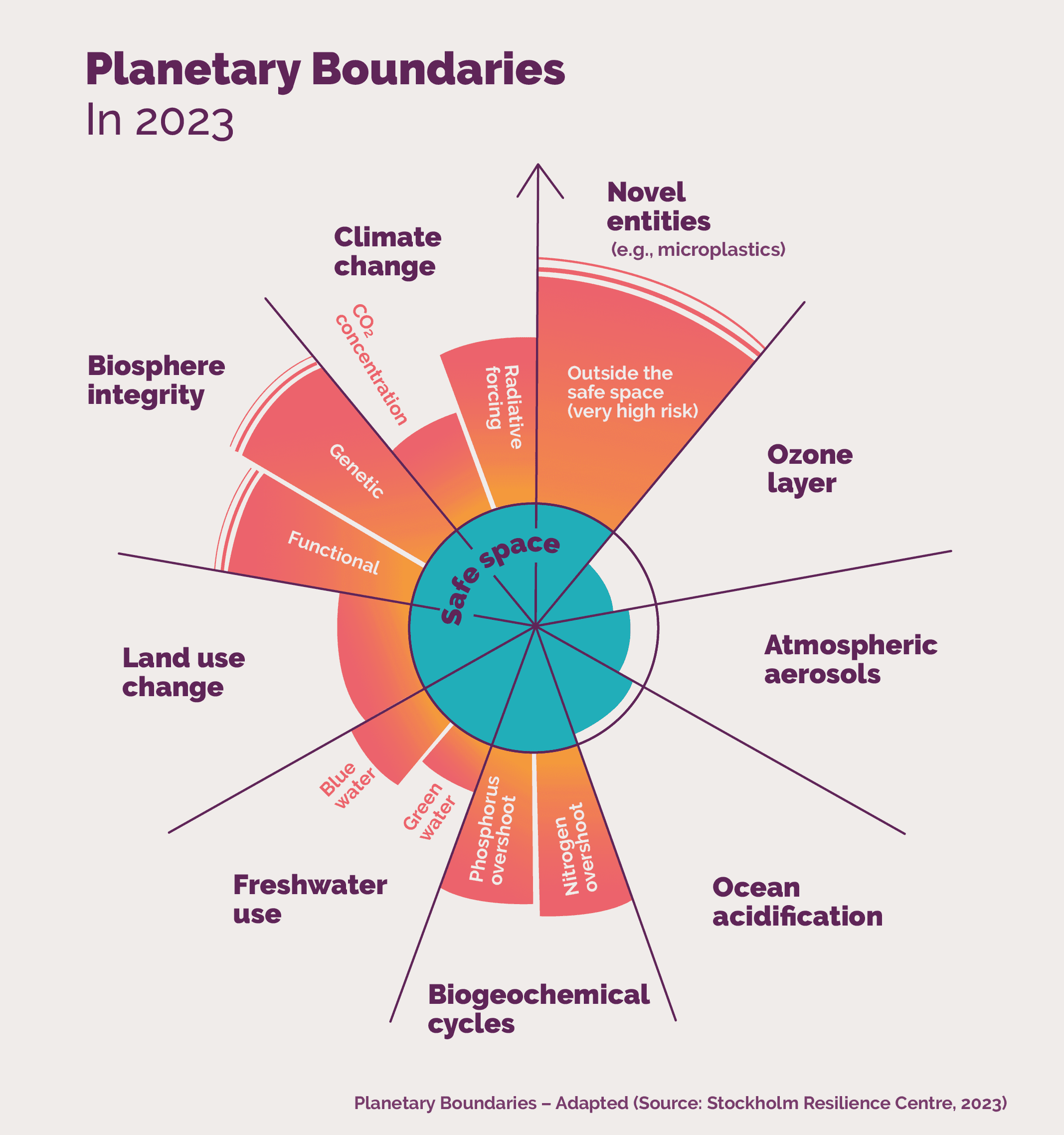

In recent decades, various indicators have been created to show the real negative impacts of human activity on the planet. The concept of planetary boundaries was introduced by Rockström et al. (2009), and since then, scientists have developed an accurate map of the Earth's system considering different biophysical boundaries, such as climate, biogeochemical cycles, biosphere integrity, and freshwater use. The current state shows that at least 6 of the 9 planetary boundaries have already been exceeded (Richardson, 2023), and continuing to operate as if we were not at risk is, at the very least, a civilizational mistake.

The negative impacts of human activity stem from our historical choices. Deforestation, intensive use of coal, oil, and their derivatives have defined the 20th and 21st centuries in ways that jeopardize our climate stability. Excessive consumption, combined with the improper disposal of various types of plastics, leaves its mark on the oceans and inside living beings in the form of microplastics. These choices can be summarized by the “take-make-waste” tripod—the foundation of our linear economy, which reflects a reductionist and utilitarian view of Earth, as if it were merely a supermarket shelf. The term “natural resources” should urgently be replaced with “natural heritage.” This conversation, too, is not new.

Concern for the planet’s natural heritage was already highlighted by British economist Kenneth Boulding in his book The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth (1966), which addresses the urgent need to rethink how we relate to the planet’s resources and to eliminate all forms of pollution and waste. I have discussed this theme further in the article ESG and Circular Economy: Coevolving Concepts.

That is, through their attentive view of the environment, Carson and Boulding challenge a development model that has been good for a few, bad for many, and harmful to the planet—becoming sources of inspiration for all who understand and desire to do things differently. With all this, the big question that remains, at least for me, is: what are we waiting for to accelerate the changes we so urgently need?

Inspiration from Nature

It is always time to rethink our choices, even those made decades ago. One of the main paths forward is to rethink the foundations on which we structure our economies. This requires a redefinition of development that genuinely considers planetary boundaries as fundamentals—not as constraints.

One of the models inspired by natural cycles and that values people and more sustainable development pathways is the Circular Economy. It proposes a revolution aimed at avoiding waste and protecting natural heritage, seeking to keep materials in use longer and at their highest quality, emphasizing processes such as recycling—and especially reuse. Along with these proposals come, as a consequence, changes in product design, emphasis on renewable energy, local production, redefinition of consumption as a life purpose, efficient waste management, and shared responsibility across all sectors to make this transformation happen. Yes, we know this is not a small task.

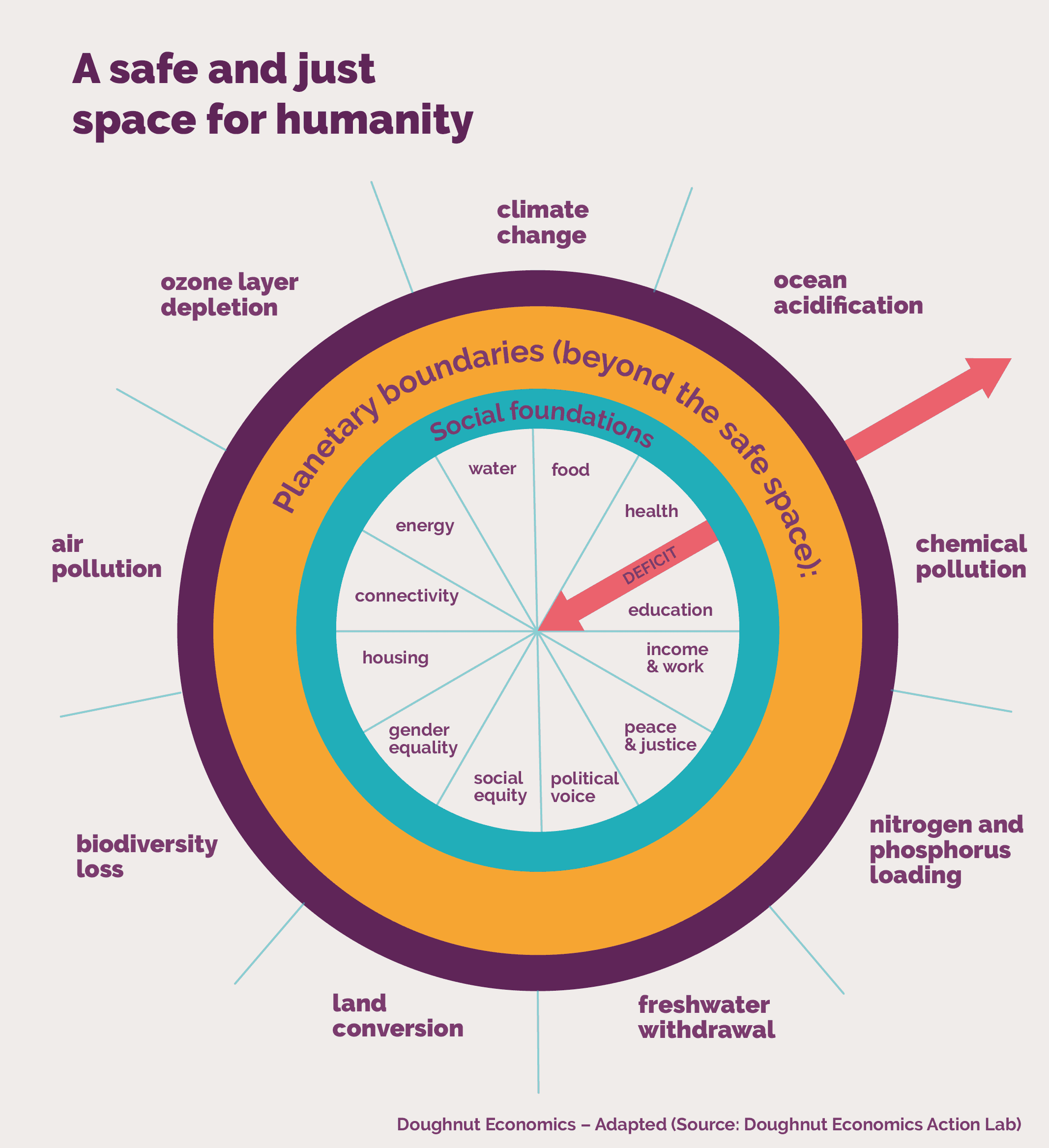

It is worth noting that, at this point in the circular revolution, we are still largely focused on technical-technological solutions for closed-loop systems. But the true 21st-century circular economy cannot be reduced to just that. Placing the circular economy in dialogue with planetary boundaries means creating regenerative and inclusive cycles. The new economy must operate like a living system, within a safe and just space for humanity—as proposed by Kate Raworth in her Doughnut Economics (2017). This model suggests we must remain between the “social foundation” and the “ecological ceiling.” Any system that does not respect these limits becomes unsustainable.

At this stage in history, we must face multiple crises as inherently social challenges, taking into account humanity’s needs and rights, as well as the consequences of our choices on the environment. The path is full of obstacles and resistance—but alternatives already exist.

Purposeful innovation: biomimicry and regenerative design

Innovating within planetary boundaries is an art. Biomimicry, for example—a field that studies nature as model, mentor, and measure (Janine Benyus, 1997)—invites us to design circular systems that imitate ecosystems. This means designing biodegradable products, sponge cities, living materials, and technologies that contribute to the restoration of natural cycles—not just minimizing harm.

More than zero waste, I’m talking about regenerative design: buildings that capture carbon, industries that restore soils, supply chains that regenerate watersheds, and companies, governments, and citizens committed to going beyond—cooperatively and dialogically.

Social Darwinism must be definitively abandoned. It is not the strongest who will survive in a circular future, but those who seek innovative forms of participation and cooperation. In nature, multiple forms of cooperation are essential for the survival of the entire ecosystem. During the dry season in the Amazon, for instance, it was once believed that trees fiercely competed for water. Today, it is known that older trees, with deeper roots, are able to draw water from deeper soil layers and share it with younger trees. To cooperate is to thrive.

By imitating nature, the success of circular companies will no longer be measured solely by profit margins, but by margins of resilience, restoration, and equity.

Culture and Circular Societies

No revolution is lasting unless it is also cultural. The culture of circularity depends on recreating our sense of purpose and relationships with time, resources, and the rhythms of life. It is about replacing the illusion of accelerated progress with the perpetuation of life within a planetary ethic. It is about learning from Indigenous wisdom, ancestral knowledge, and community practices, recognizing that sustainability is not only technical, but also spiritual, aesthetic, symbolic (and urgent).

Combining planetary boundaries with the principles of regenerative circular economy leads us to the most radical form of innovation: not the one that promises a “green solution,” but the one that teaches us to value legacy and intergenerational respect with awareness and responsibility.

Circular societies are less about materials and more about purpose and meaning. And within the boundaries of the planet, we discover the true space of creativity: the one where we design the future with collective vision and imaginative courage.

I know this entire conversation may still sound utopian to many. But it is important to know that many micro-transformations are already happening—and that great revolutions have never started with a large number of people. Just look online: COP30 in Brazil, the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, the Sustainable Development Goals, and, this Environment Month, the urgent campaign to “End Plastic Pollution.”

And you?

What can be your circular cause—starting today?

*Profº Dr. Edson Grandisoli

Ambassador and pedagogical coordinator of the Circular Movement. He holds a Master’s degree in Ecology, a PhD in Education and Sustainability from the University of São Paulo (USP), and a Postdoctoral degree from the Global Cities Program (IEA-USP). He is also a specialist in Circular Economy from the UN’s UNSCC. Co-creator of the Schools for Climate Movement, he is a researcher in the field of Education and associate editor of the journal Ambiente & Sociedade.

*This text was automatically translated using artificial intelligence and subsequently reviewed. However, minor differences may still exist when compared to the original version in Portuguese.